The white wedding dress wasn’t originally African and came with rules about purity, status, and tradition that many brides are now rethinking. But how did it become a default look in the first place?

African weddings have always been celebrations of life, community, and heritage—a tapestry of color, music, customs, and meaning. Imagine a Ghanaian bride in a bright kente gown walking down the aisle with her father, also wrapped in kente cloth, or a Nigerian bride dressed in shimmering iro and buba, beads glinting in the sun. Those are weddings rooted in stories, identity, and culture.

Yet for many African women, something strange has happened over time: the expectation that their most important day should also look “white.” In Ghana, there’s a growing wave of brides rejecting the classic white dress in favor of cultural fabrics, often pairing Kente gowns with veils or jewelry that honors their roots. When you scroll through real‑wedding galleries and see these brides, it raises a simple question: if tradition here was already rich, why did we let a foreign “ideal” become the standard?

That’s the question this article explores. We will go back to where the white gown idea began, follow how it spread across continents—including into African ceremonies—and look at what’s changing today. We’ll also compare with wedding traditions in other cultures around the world and reflect on what it means when modern brides choose heritage over convention.

The Origin of the White Wedding Dress

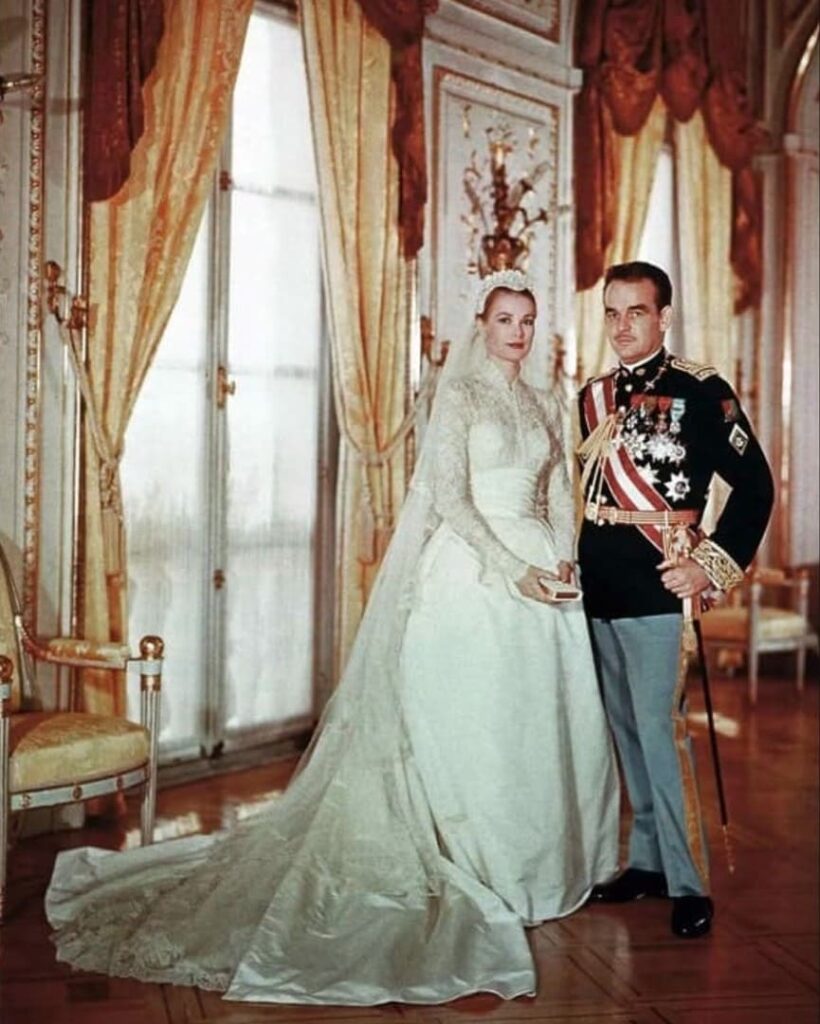

The story most often told begins in 1840, when the then twenty-year-old Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom married her cousin Prince Albert.

The royal wedding of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert was held on Sunday, February 10, 1840. At 11:45 a.m., the fiancé’s procession left Buckingham Palace for St. James Palace. Around noon, the young woman left for the Royal Chapel with her mother, the Duchess of Kent, and the Duchess of Sutherland, mistress of the royal wardrobe.

But, to everyone’s surprise, Victoria wore a beautiful white satin dress from Spitalfields, a London neighborhood famous for its high-end silk. It was covered with beautiful lace by artisans from Honiton, a village in Devon, known since the Renaissance for its crafts. The long dress, fitted at the waist, was very flared, with a train and bare shoulders. It opened the way for voluminous dresses with a large number of accessories.

At the time, her decision seemed strange because white was not a typical wedding color. Dresses for brides had long been in all kinds of hues: red, green, blue, even practical shades like grey, brown, or black, depending on class and economy.

There were practical reasons for that. Laundry was difficult; water and soap were harsh and expensive, and streets were muddy. A white dress was almost guaranteed to stain, making it impractical for regular use. Most brides simply wore their finest existing dress or commissioned one they wouldn’t mind re‑wearing for other events.

Queen Victoria’s wedding changed that. Because hers was a highly visible union and widely publicized, her white dress became the new symbol—a fashion statement—rather than a practical choice.

Her choice didn’t stem from a deep symbolic belief in purity or virginity (at least not officially), but more from a desire for elegance, simplicity, and highlighting the lace and craftsmanship of the gown.

Even though photography did not yet exist at the time of Queen Victoria’s wedding, several paintings published in the newspapers depicted the royal dress marvelously well.

Still, as the trend spread across Europe and eventually to America, it took on deeper meanings. White began to be associated with innocence, purity, and modesty—a set of social values that fitted well with the moral codes of the time.

By the early 20th century, the white wedding dress had moved beyond elite circles. After the economic boom post‑World War II, many middle‑class women began embracing it too, relying on more affordable fabrics and ready‑made dresses.

By then, the “white wedding”—the full ceremony centered around a white‑gowned bride—had become a global norm, exported far beyond Europe and America.

Before Queen Victoria’s wedding, brides often wore dresses in a wide range of colours, chosen for practicality, symbolism, or personal preference. In the 16th century, green was particularly popular because it symbolized fertility and renewal. In later centuries, darker colours were sometimes preferred; black or dark wool dresses were occasionally worn, often because they were practical, durable, and reusable. One notable example is Laura Ingalls Wilder, who married in black cashmere simply because it was part of her trousseau and could be worn again, reflecting the practical mindset of many brides at the time.

The White Wedding: A Borrowed Tradition

It’s important to draw a distinction: the “white wedding” as a concept—a formal ceremony featuring a white‑gowned bride, a veil, and typically church vows—is different from more traditional or cultural weddings. The “white wedding” is a Western export.

When Western missionaries, colonial structures, and media influence spread across Africa, so did this template. Western‑style weddings came to be seen by many as “modern,” “proper,” or “prestigious.” The white gown became not just a fashion choice but a signal, a badge of status, assimilation, and acceptance.

What’s more, the meaning assigned to white purity, virginity, and modesty found fertile ground in conservative Christian and social frameworks. Over time, the white wedding gown wasn’t just popular; it became the default.

That default was often uncritically adopted. In many African settings, the white gown became the measure of a “real wedding,” overshadowing local customs and erasing centuries‑old traditions.

Why White Became the Default in Africa

White became the “standard” choice for African brides on their Big Day for several reasons. These included:

1. Religious and colonial influence:

Churches encouraged Western wedding ceremonies; colonial administrations set Western norms as “civilized.”

2. Family expectations and social pressure:

A white wedding often signaled social status and respectability. Families who adopted Western‑style weddings showed alignment with perceived progress or modernity.

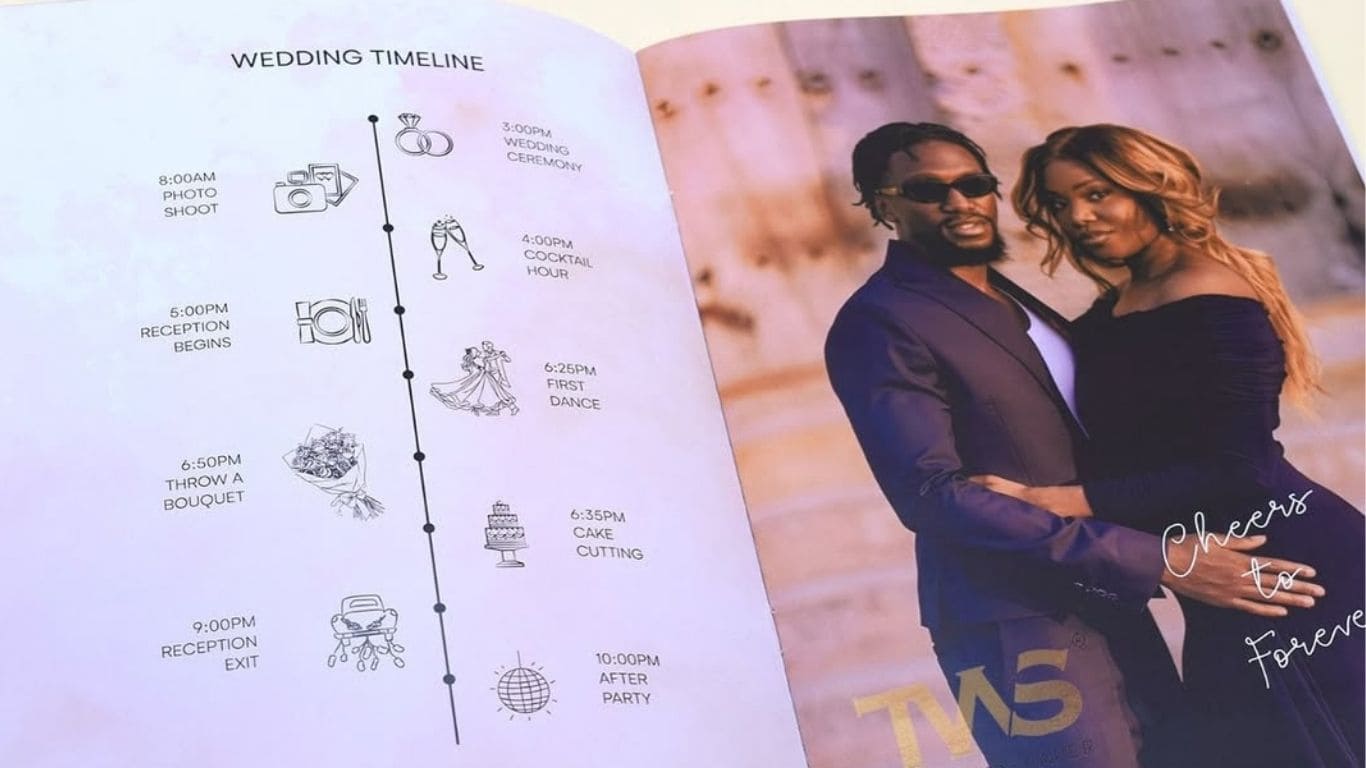

3. Media, photography, and fashion books:

Magazines, photos, and movies (often showing brides in white gowns) shaped aspirations. Suddenly, white weddings looked like the ideal or “normal.”

4. Association with purity/virginity:

Over time, white dresses became connected to the idea of virgin brides—reinforcing notions of morality, honor, and tradition.

In many African communities, the white gown was adopted wholesale—not because it resonated with cultural traditions, but because it had been framed as “the right way” to marry.

Traditional African Weddings: What We Lost

To put the adoption of white gowns into perspective, consider what many Africans used to (and still do) have: weddings deeply rooted in heritage, symbolism, and community rituals.

Take Ghana, for example: the central wedding ceremony is often the “Knocking Ceremony” (known locally as “Opon‑akyi bo” or “kokooko”). In this ritual, the groom (or his family) visits the bride’s home to formally request her hand in marriage. They bring gifts, meet the family elders, and engage in speech, songs, and negotiations. Once terms are agreed upon—sometimes including a traditional “dowry” or bride price—the union is sealed.

This tradition places emphasis on family, community, respect for elders, and mutual agreement. The bride is central, but so are her heritage, background, and identity. Her wedding attire was never about conforming to a foreign ideal—it was about honoring culture.

Across Africa, from West to East, marriages followed similar culturally specific customs: negotiation of bride price, family involvement, and traditional ceremonies—not a Western church aisle. Many African cultures did not have a “white‑gown moment.” Instead, their weddings were defined by ritual, community, music, food, and ancestral blessings.

What happened when Western‑style weddings arrived was that many of those traditions got sidelined, simplified, or replaced. The white gown became the visible symbol of that shift.

@osei_douglas Exchange of vows

♬ original sound – Douglas

@eventswithnyame This is breathtaking 😚❤️!!! #SeEd25 #AMondayAffairAt26 #fyp #foryou #foryoupage #foryourpage #fypage #explore #explorepage #following #followingpage #goviral #viral #viralvideo #eventswithnyame ♬ Doing Of The Lord – Moses Bliss & Nathaniel Bassey

The Cultural Rules Around Bridal Colours in Africa

African weddings are diverse, and color has always held meaning. Black, for instance, is often prohibited because it can symbolize mourning or bad luck. White, conversely, became associated with new beginnings, especially in Christian weddings.

Yet these rules contrast sharply with traditional African attire, which celebrated vibrant patterns, textures, and symbolism. Before Western influence, brides could wear a wide range of colors to signify fertility, wealth, and family heritage—a far cry from the uniformity of the white gown.

A Global Perspective: Brides Who Don’t Wear White

It’s helpful to remember that white wedding gowns are not universal. Around the world, many cultures have their own wedding colours and customs.

- In China, brides have traditionally worn red, a colour symbolizing luck, prosperity, and joy.

- In India, red remains deeply rooted in wedding ceremonies: the red sari or lehenga is worn to signify fertility, prosperity, and marital bliss.

- In Korea, traditional bridal wear (hanbok) often features vibrant colours and symbolic patterns rather than white gowns.

These traditions show that the idea of a white dress as the “proper” wedding attire is not human nature; it’s a cultural construction. And for many cultures, including much of Africa, the white gown is an import, not an origin story.

@joanurban_kente1 ♬ original sound – URBAN KENTE OUTFITTERS

The Virginity Myth and White Dresses

One of the more harmful ideas tied to white weddings is the expectation that the bride must be a virgin; white was conflated with purity. That association didn’t exist originally; it evolved as part of the social and religious framing of marriage in Western contexts.

As that expectation came to Africa, it introduced pressure, judgment, and shame into weddings, turning what should be a celebration of love into a test of purity or morality.

Today, more people are questioning that myth. They argue that identity, culture, and individuality should matter more than archaic norms about what a wedding “should” look like.

Reclaiming Tradition: Moving Beyond White

There is a growing movement among African brides to reclaim their heritage through wedding attire. In Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, Tanzania, and beyond, couples are reimagining what a wedding can look like: colourful, meaningful, and culturally authentic.

These weddings don’t reject faith or ceremony. Instead, they blend modern love stories with ancestral tradition. Brides and grooms are choosing Kente, aso‑oke, shweshwe, beadwork, traditional jewellery, and fabrics that tell their story. Sometimes they combine traditional fabrics with modern silhouettes; other times they go full cultural — heart, soul, and cloth.

Social media and wedding blogs are playing a big role. Real couples are sharing real weddings, showing the world that beauty, dignity, and tradition don’t have to come wrapped in white satin. For many, the wedding day isn’t about imitation. It’s about identity.

Conclusion

White isn’t wrong. It’s not evil. But it’s also not the only way.

We’ve inherited white weddings as part of a borrowed tradition, one shaped by Western aristocracy, colonial influence, and media glamour. What this article shows is that African brides don’t have to accept that standard. They have the freedom, and many are already using it, to choose gowns that reflect who they are, where they come from, and what they value.

Whether a bride chooses white, Kente, aso‑oke, or shweshwe, what matters is that she’s making a choice rooted in identity, pride, and authenticity. More importantly, the wedding should be about two people committing their lives, not about fitting a mould that never belonged to them.