Bride price, or lobola in South Africa, is a centuries-old marriage tradition. This guide explains typical costs, how negotiations work, refund possibilities, and what the law says.

So you’ve met a South African woman, gotten to know each other, and somewhere along the way, friendship turned into something real. Or maybe you’re South African yourself, and you’re standing at that point where marriage conversations are no longer hypothetical. Either way, once things start getting serious, one word shows up fast and stays in the room: lobola. If you fall into either category, this article is for you.

Before the venue searches, the mood boards, and the luxury wedding ideas you’ve been saving, there’s something far more important to understand. In South Africa, marriage doesn’t start with a celebration. It starts with tradition. Lobola isn’t just a formality or a box to tick. It’s a deeply rooted custom that carries meaning, expectations, and family involvement.

For many couples, this is where confusion begins. How much is expected? Who negotiates? Is it symbolic or financial? Can it be paid in cash? These questions come up quickly, especially when families from different backgrounds or cultures are involved. And while the tradition has evolved, its significance remains strong.

To truly understand lobola, you first need clarity on what it is—and what it isn’t. Many people use terms like “bride price” and “dowry” interchangeably, but they don’t always mean the same thing in a South African context. That distinction matters, and it shapes how families approach the process from the very beginning.

Difference between Lobola, Bride Price, and Dowry in South Africa

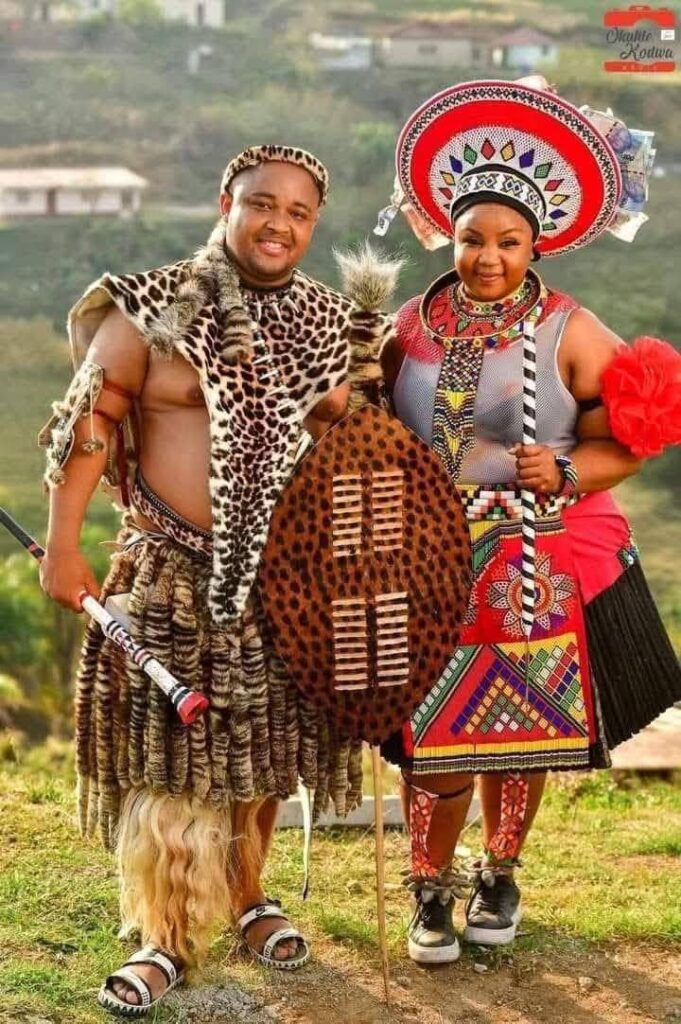

In South Africa, lobola and bride price are the same thing. The difference is mostly in language, not meaning. Across cultures, the tradition takes different names—bogadi in Setswana, bohali in Sotho, mahadi in Sesotho, magadi in Sepedi, and roora in ChiShona—but the idea remains consistent. It’s a symbolic gesture from the groom’s family to the bride’s family, rooted in respect, gratitude, and the formal joining of two families.

Where confusion usually starts is with the word dowry. In everyday conversations, people often use “dowry” to describe “lobola,” but culturally, they are not the same thing. Dowry is a different system altogether, with a different direction of exchange and a different purpose. Understanding this distinction matters, especially when navigating marriage conversations across cultures, families, or even borders.

Once you accept that “lobola” and “bride price” refer to the same practice in South Africa, the real comparison becomes clear: lobola versus dowry. They may both appear in marriage discussions, but they operate on very different principles. To make sense of it all, it helps to break down how each system works, who is involved, and what each tradition is meant to represent.

Below is a clear, practical breakdown of the key differences—so you’re not just repeating terms but actually understanding the tradition behind them.

Key Differences Explained

1. Who Gives What

Lobola, also known as bride price, is given by the groom’s family to the bride’s family. It’s a gesture of appreciation for raising the bride and welcoming her into a new household. Dowry works in the opposite direction. Traditionally, it involves the bride’s family providing wealth, goods, or support to the bride or the couple as they start their life together.

2. Direction of Value

With lobola, value flows toward the bride’s family as a sign of respect and commitment. Dowry, where it exists, flows toward the bride or the new household, meant to support her financial security within the marriage. This difference alone changes the meaning of the entire process.

3. Cultural Practice in South Africa

In South Africa, the dominant and culturally rooted practice is lobola. While some people casually use the word “dowry,” what is actually practiced across most communities is bride price in its traditional sense. Dowry, as a system, is not historically central to South African marriage customs.

4. How the Amount Is Decided

Lobola is typically negotiated between families or their representatives. The process is guided by tradition, family circumstances, and mutual respect, not rigid price lists. Dowry, in cultures where it exists, is often predetermined by family expectations or social norms rather than negotiated between both sides.

5. What Is Included

Lobola may be paid through cattle, cash, or a combination of both, sometimes alongside symbolic gifts. Each item carries meaning beyond its monetary value. Dowry traditionally includes household goods, land rights, jewelry, or financial assets intended for the bride’s use or security.

6. Purpose of the Tradition

Lobola is about relationship-building. It formalizes the union between two families, acknowledges parental roles, and signals serious intent. Dowry, on the other hand, is centered on economic support for the bride, often reflecting concerns about stability and inheritance within marriage.

7. Modern Interpretation

Today, lobola in South Africa is often more symbolic than transactional, especially in urban or intercultural marriages. Many families prioritize respect, communication, and unity over strict figures. Dowry, where still practiced globally, continues to carry varied interpretations, sometimes cultural, sometimes economic, depending on the society.

What this really means is that when people talk about dowry in South Africa, they’re almost always referring to lobola. Understanding that distinction makes conversations about marriage, expectations, and costs far clearer—and far less stressful.

What Is the Lobola System in South Africa?

Lobola is a marriage system that has existed for centuries across Southern African cultures. At its core, it is a form of bride wealth: a premarital process where the groom’s family formally approaches the bride’s family to express appreciation, respect, and serious intent. Long before white weddings and legal ceremonies, lobola was the step that made a marriage socially recognized. Even today, many families still see the wedding as an addition, not the foundation.

What often gets misunderstood is the idea that lobola is simply about money. It isn’t. Lobola is a symbolic exchange that publicly binds two families together. It acknowledges the role the bride’s family played in raising her, affirms the groom’s readiness to take responsibility, and creates a relationship between families that extends beyond the couple themselves.

The process is usually handled through formal negotiations, led by elders, uncles, or appointed representatives, not the couple directly. These discussions are deliberate and respectful, guided by tradition rather than speed. Traditionally, cattle were exchanged, but in modern South Africa, this has evolved. Today, lobola may be paid in cash, livestock, goods, or a combination, depending on family customs, location, and circumstances.

While the specifics vary across communities—Zulu, Xhosa, Sotho, Pedi, Tswana, Venda, and others—the meaning remains consistent. Lobola signals commitment, respect, and legitimacy. It also plays a practical role: in many families, the resources received help fund the wedding, support the new household, or contribute to broader family responsibilities.

For younger generations, lobola can feel confusing or even intimidating, especially when it’s discussed only in terms of cost. That confusion often comes from a lack of open education around the tradition. When the purpose isn’t clearly explained, it’s easy to reduce lobola to a transaction. In reality, it is meant to be a process of unity, one that prepares both families—and the couple—for marriage.

Modern South Africa has added new layers to the system. Intercultural and interracial marriages are increasingly common, and lobola negotiations now often involve families with different languages, customs, and worldviews. Yet even in these cases, the process still does what it has always done best: it creates space for dialogue, respect, compromise, and shared responsibility.

At its best, the lobola system isn’t about numbers or pressure. It’s about intention. It’s about two families choosing to come together, honor tradition, and lay a foundation strong enough to carry a marriage forward.

Is Lobola Legally Binding? What Does South African Law Say About It?

Here’s the thing. Lobola isn’t written out line by line in South Africa’s law books, but it absolutely carries legal weight. Under the Recognition of Customary Marriages Act, lobola is widely accepted as proof that a customary marriage exists. In simple terms, when families have properly negotiated and agreed on lobola, the law often treats that as strong evidence that a real marriage has taken place. Still, it’s important to be clear about one thing: lobola is not buying a bride. Legally and culturally, it’s about respect, acknowledgment, and formally joining two families.

South Africa operates under both civil law and customary law, and lobola falls firmly within the customary framework. For it to count, certain basics must be in place. Both partners must be adults, able to consent, and the process must follow the customs of the families involved. Consent matters a lot. If either person is forced, pressured, or manipulated, the marriage can be challenged. The same applies if negotiations are handled recklessly or in bad faith. The law isn’t interested in tradition being used as a weapon.

There’s also the question of fairness. Courts have made it clear that lobola should be reasonable. If an amount is clearly meant to punish, exploit, or financially break the groom’s family, it can be disputed. And yes, if lobola is agreed on and not paid, families can take the matter further legally, especially if the marriage is already being recognised as valid. But even then, the goal isn’t punishment. It’s accountability.

What this really means is that lobola lives in two worlds at once. The law recognises it, but it doesn’t reduce it to paperwork. It remains a cultural process first, legal proof second. When done with honesty, consent, and respect, lobola strengthens a marriage rather than complicates it. And when people approach it with understanding instead of fear, the legal aspects usually take care of themselves.

The Cost of Lobola in South Africa

Here’s the thing most people don’t tell you upfront: lobola has no fixed price. There’s no national rate card, no official calculator, no universal structure. The cost shifts from one family to another, one tribe to the next, even from one household to its neighbour. What’s asked is shaped by culture, values, expectations, and reality. Things like the family’s traditions, economic background, location, the bride’s life path, and even how the families relate to each other all come into play. That’s why two people from the same community can pay wildly different amounts, and both still be considered “correct.”

How much does lobola cost in South Africa?

Per JanaTribe’s findings, the average modern lobola negotiations tend to land anywhere between R50,000 and R100,000, or the traditional equivalent of 5 to 15 cows. In some cases, especially where both families are financially comfortable, or tradition is taken very seriously, the amount can push well beyond six figures. At the same time, many families today intentionally keep lobola affordable. You’ll increasingly see symbolic amounts like R30,000 or less, agreed on to honour culture without financially suffocating the couple.

Traditionally, cattle were the currency. Ten cows are still commonly referenced as a starting point, even when no actual cows change hands. Today, cash is widely accepted, often calculated as the monetary value of those cattle. Installment payments are also common, giving the groom’s family breathing room while still respecting the process. What matters is the intention, not the format.

That said, conversations around cost are rarely neutral. Families may consider the bride’s education, whether she has children, her marital history, and sometimes even outdated ideas like virginity. In some homes, her role as a breadwinner or her future earning potential enters the discussion. In tougher economic times, families are becoming more realistic, choosing figures that won’t turn the start of a marriage into a lifelong debt sentence. Still, in an inflated economy, even “reasonable” amounts can feel heavy.

To ground this in real-world numbers, here’s what people and platforms have reported over the years. Keep this skimmable, not definitive:

- Franc App estimates place lobola anywhere from R10,000 to R100,000, with extreme cases reaching R400,000.

- A 2015 estimate cited an average of 12 cows or R82,000 in Gauteng, which today would likely exceed R100,000.

- Prenup ZA suggests common cash ranges of R20,000 to R50,000, or 10 cattle or more.

- Reddit users consistently report figures between R50,000 and R100,000, with examples like R75k, R85k in 2019, and R80k–R100k being described as “normal.”

- One detailed breakdown from a bride’s family projected around R67,000, rising to nearly R97,000 once rings, attire, and cultural expectations were factored in.

All of these point to one truth: lobola is less about objective pricing and more about perceived value. That’s why clarity from the bride’s family matters so much. When expectations are explained openly, negotiations tend to feel respectful rather than tense.

@tshego_chale22 To a new chapter in life 📖 #traditionalwedding #lobolanegotiations #mocambicanweddings #southafricanweddings ♬ original sound – Tshego Chale

Lobola Amount Breakdown by Major South African Communities / Provinces

While exact figures vary, broader patterns do show up across regions:

- Gauteng: Around R82,500 or 12 cows

- Eastern Cape: Roughly R85,000 or 15 cows

- KwaZulu-Natal: About R78,000 or 10 cows

- North West: Close to R65,000 or 8 cows

- Northern Cape: Often lower, around R30,000 or 5 cows

Some wider context helps make sense of this:

- Up to 80% of Black South African couples who identify with traditional customs still engage in lobola negotiations.

- In cities, 50–60% of couples use cash, sometimes alongside symbolic cattle.

- Payments commonly range from R10,000 to over R100,000, depending on class and expectations.

- Among millennials, lower amounts and flexible payment plans are becoming the norm, driven by student debt, rent, and real-world economics.

Lobola hasn’t disappeared. It’s adapted. And the fact that families are renegotiating how it works, rather than abandoning it, says a lot about how deeply rooted it still is.

Can Lobola Be Refunded?

Can lobola money be returned? That’s usually the first question people ask when a marriage starts to fall apart, and the honest answer is: it depends. Lobola isn’t treated like a receipt-based transaction where money automatically goes back if things don’t work out. Once families have been formally joined, undoing that bond is emotional, cultural, and deeply situational. That’s why refunds are never automatic and are almost always decided through family discussions, guided by custom rather than impulse.

Traditionally, fault plays a big role. If the husband is seen as the cause of the breakdown through abuse, abandonment, or infidelity, most customs are clear that he cannot demand lobola back. The thinking is simple: you don’t reclaim gratitude after you’ve dishonoured the family that trusted you. On the other hand, if the wife is found to have seriously violated the marriage, some communities may allow a partial or full return, depending on what happened and how long the marriage lasted. Even then, it’s rarely straightforward.

There are also situations where no one is fully to blame. When couples separate by mutual agreement, families usually sit down and negotiate what feels fair. They might consider whether children were born, how many years the marriage lasted, and what the groom’s family continued to contribute over time. In cases of death, customs differ widely. Some families may return part of the lobola, others may not, especially if children are involved.

What matters most is this: lobola is about relationships, not refunds. Every situation is handled on its own merits, shaped by culture, context, and conversation. When things end, families are expected to act with maturity and dignity, remembering that even a broken marriage once represented unity, respect, and shared history.

Lobola Negotiation in South Africa: How It Really Works

Here’s the truth: most people only learn halfway through the process: lobola is not a bill you’re handed. It’s a conversation. A structured one, yes, but still a conversation shaped by culture, respect, and relationships between families.

Once both families agree to move forward, each side appoints representatives. Traditionally, this means senior male relatives. Fathers, uncles, or trusted elders who know the customs and know how to speak carefully. The couple themselves usually stay out of the room. Not because their voices don’t matter, but because lobola is about families meeting families, not lovers negotiating their own future.

Why the negotiators matter so much

You don’t just send anyone. A good negotiator understands the culture of the bride’s family, knows when to push and when to pause, and can read the room. He also knows your limits. That part is crucial. Before any meeting happens, your side quietly agrees on what’s realistic financially. That number doesn’t get announced, but it guides every response that follows.

On the bride’s side, their representatives do the same. They protect family dignity, honour their daughter, and ensure tradition is respected. This balance is what keeps the process from turning hostile.

Where the real negotiation happens

The discussion happens during a formal family meeting, often announced in advance and carried out with ritual seriousness. Expect a bit of drama. The bride may be described as priceless. The family might say they’re not sure they’re ready to name a figure yet. A high opening amount may be mentioned, sometimes in cows, sometimes already converted into cash.

This isn’t greed. It’s a theatre. It sets the tone and creates space for negotiation. Your representatives respond slowly, respectfully, often stepping aside to consult privately before coming back with a counteroffer. The back-and-forth continues until both sides feel the agreement reflects respect, not pressure.

Cash, cattle, and how payment works today

Traditionally, cattle were central. Today, cash is far more common, especially in urban and interprovincial marriages. Many families still speak in cattle terms even when they expect money. Ten cows might simply mean the cash value of ten cows.

Installments are normal. Families may agree on a total amount, with part paid upfront and the rest over time. What matters is transparency and follow-through. Breaking your word causes far more damage than negotiating a lower amount honestly.

Who needs to be present?

While customs vary, representation usually includes:

- Senior male relatives or elders

- At least one parent figure

- Often an aunt or respected female elder

- A small supporting group from each side

If distance, finances, or family structure make this difficult, symbolic representation is often accepted. What families look for is effort and respect, not perfection.

What to keep in mind

Lobola negotiations are not about winning. They’re about setting the foundation for a marriage that will last. Families watch how you show up. Your patience. Your humility. Your seriousness. Handle the process well, and you earn something far more valuable than approval for the wedding. You earn trust.

And that, more than the amount agreed on, is what carries the marriage forward.

Final Thoughts

Lobola is often talked about like a number, but that’s the shallow version of the story. When you really sit with it, you realise it’s a system built to slow people down, force conversations, and bring families into the marriage long before the wedding day. The negotiations, the back and forth, the symbolism, even the disagreements all serve one purpose: to make sure a union doesn’t start in isolation. In a time where relationships can feel disposable, lobola insists on intention, accountability, and respect.

That said, traditions only survive when they are understood, not feared. Modern couples are navigating student loans, rent, blended cultures, and global lives, and many families are responding with flexibility and wisdom. When lobola is approached as a bridge rather than a burden, it does what it has always done best: unite families, honour heritage, and set a marriage up on something deeper than celebration alone.